The Palaeolithic Age

Firstly, it should be understood that evolution is not through heredity alone, rather, there are some genes that lay dormant until certain environmental and circumstancial changes trigger them. In essence this is the nature of adaptation. Too much inbreeding however, results in what is a called a “genetic bottleneck” in which some of these genes are either lost or mutate. It can be due to isolation, or depopulation through disaster or disease. Either way the genetic rule of thumb is that wherever there is convergence there is subsequent divergence. That means the extinction of one species gives another the opportunity adapt in various ways, increasing its chances of survival through at least one of those variations, as was the case between the Neanderthal and the Cro Magnon. That does not say one was more cunning than other, rather each was ideally to suited to their own climate and living conditions at the time until that changed dramatically.

Genetic studies have substantiated that the first Proto Europeans were the Cro Magnon, who were also the first homo-sapiens-sapiens. Their culture is referred to as Aurignacian and, in Europe, began around 45,000 BP as they spread forth east and west beyond the Balkans. For the most part they were largely communal cave dwellers well known for their paintings, animal carvings, flutes made of bird bone and especially the “Lion Man”: the oldest known anthropomorphic figure ever carved. Much of these activities were conducted at the remote end of cave systems, evidently as a sacred space for their rituals. Burials, however, were done closer to the entrance, the bodies fully dressed, whereas whatever personal effects were buried with them seems an indication of social status . Tools of bone and antler were standard, whereas flint and obsidian served well as carving blades. This period also saw the first developments of fired clay. The map below shows the global spread of early modern humans:

The Gravettian Culture is a branch of these people that diverged with the glacial maximum around 26,500 to 18,000 BP becoming more skilled at hunting the mammoth, taking to a life of following the herds and making shelters of their massive bones and hides. They were also notable for their fishing and trapping innovations, using barbed hooks and spearheads, weaving nets and baskets, and domesticating wolves as a hunting aid. Typical of their carvings were a variety of different fertility talismans. However, while some historians assume the large number of Venus figurines suggests a mother goddess cult, little is mentioned of all the male phallic figures also found- many illustrating elaborate tattoos. During this period their Aurignacian relatives withdrew to southwesterly enclaves around the Iberian Peninsula and southern France to become the Solutrean Culture, of similar large game hunters. Genetic studies have substantiated that the first Proto Europeans were the Cro Magnon, who were also the first homo-sapiens-sapiens. Their culture is referred to as Aurignacian and, in Europe, began around 45,000 BP as they spread forth east and west beyond the Balkans. For the most part they were largely communal cave dwellers well known for their paintings, animal carvings, flutes made of bird bone and especially the “Lion Man”: the oldest known anthropomorphic figure ever carved. Much of these activities were conducted at the remote end of cave systems, evidently as a sacred space for their rituals. Burials, however, were done closer to the entrance, the bodies fully dressed, whereas whatever personal effects were buried with them seems an indication of social status . Tools of bone and antler were standard, whereas flint and obsidian served well as carving blades. This period also saw the first developments of fired clay. The map below shows the global spread of early modern humans:

For further reading: http://www.humanjourney.us/PaleolithicBeginnings.html

The Mesolithic Age

The Ice Age gradually declined between 20,000 and 18,000 BP. Populations that had been restricted to the Franco-Cantabrian region progressed slowly up the Atlantic coast and major river valleys within the subcontinent, still hunting big game. This period saw aesthetic refinements in stone working and tool making, bone needles for sewing garments skills. Mollusks which also made a part of their diet, provided the use of their shells for personal adornment, along with bone, ivory and various animal teeth, fashioned into beads and sometimes even pigmented. Aside from cave painting were bas-reliefs carved into stone, some illustrating animist rituals. As climate warmed considerably around 12,000 BP the mammoth herds began declining and sea levels began to rise dramatically. The land-bridge between the British Isles and mainland Europe eventually became submerged, forming the North Sea. Of the more nomadic hunters, some moved northwards with the Mammoth, others began domesticating reindeer, horses and cattle along the way. The rest eventually settled down to land clearing and building communities of thatched huts, peat and rock shelters, domesticating cereals and other foodstuffs, smaller game such as sheep and goats. Archaeological digs at Gobekli Tepe, Turkey, established that this period also marked the beginnings of megalithic culture throughout Europe well before agriculture was established. The massive stone carvings of various animals that once dominated these regions seem almost a memorial to the dying savannas under the dramatic effects climate change during this time. Rather it was this change that made farming and domestication a necessity in order to survive in a destabilized ecosystem.

For further reading: The Ice Age gradually declined between 20,000 and 18,000 BP. Populations that had been restricted to the Franco-Cantabrian region progressed slowly up the Atlantic coast and major river valleys within the subcontinent, still hunting big game. This period saw aesthetic refinements in stone working and tool making, bone needles for sewing garments skills. Mollusks which also made a part of their diet, provided the use of their shells for personal adornment, along with bone, ivory and various animal teeth, fashioned into beads and sometimes even pigmented. Aside from cave painting were bas-reliefs carved into stone, some illustrating animist rituals. As climate warmed considerably around 12,000 BP the mammoth herds began declining and sea levels began to rise dramatically. The land-bridge between the British Isles and mainland Europe eventually became submerged, forming the North Sea. Of the more nomadic hunters, some moved northwards with the Mammoth, others began domesticating reindeer, horses and cattle along the way. The rest eventually settled down to land clearing and building communities of thatched huts, peat and rock shelters, domesticating cereals and other foodstuffs, smaller game such as sheep and goats. Archaeological digs at Gobekli Tepe, Turkey, established that this period also marked the beginnings of megalithic culture throughout Europe well before agriculture was established. The massive stone carvings of various animals that once dominated these regions seem almost a memorial to the dying savannas under the dramatic effects climate change during this time. Rather it was this change that made farming and domestication a necessity in order to survive in a destabilized ecosystem.

http://www.academia.edu/299499/Reassessing_the_mitochondrial_DNA_evidence_for_migration_at_the_Mesolithic-Neolithic_transition_2008_

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doggerland

http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2011/06/gobekli-tepe/mann-text

http://www.nextnature.net/2009/04/mapping-a-lost-world/

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UcB4PpjRFNY

An elementary knowledge of our megalithic ancestors

For much of his lifetime a chap named Pierre Mereux did a field study of the vast megalithic rows between Carnac and Le Ménéc in the Bretagne region of France. This, he so meticulously surveyed by every means possible at the time and carefully documented. Needless to say, a most valuable document to professional researchers in this field of archeology to this day. The most fascinating aspect of his observations was that these huge menhirs were erected along tectonic fault lines and made of stone types that could channel their geostatic forces such that EMF was highly measurable wherever the focus of these stress forces happened to surface through the molecular resonances of these stones. It seems bluestones were particularly favoured for those properties. A kind of megalithic Feng-shui, you could say...but especially interesting is the paranormal phenomena experienced where these energies are being actively channelled. Indeed these describe the mysterious otherworldly portals we hear of in Celto-Germanic legend, something the megalithic builders obviously had down to a very basic yet highly evolved science. Looking at the strange spirals found in so many ancient burial chambers, it becomes clear how these ancients understood reality as a matrix of very fluid and transmutable energies through resonance- although I’m sure they described all that in quite different words. A language based on its own integral understanding of these things- quite without the schisms between science and spirituality typical of our so-called new world order.

http://www.neara.org/ROS/roscarnac01.htm

http://www.neara.org/ROS/roscarnac02.htm

Although I am not a fan of crystal reiki, there’s a lot to be said about the molecular properties of quartz- something that long had its place in alchemy for its pizo-electric effects. In German lore about the “Bergkristall” it was said you should rub it on velvet before making an invocation. I liked to use sizeable round clacking stones of white granite from the Greenland formation, for dispersing or focusing energies in an outdoor workspace- a widdershins spiral inwards to focus. Nova Scotia was a real treasure trove for such mineral delights on its shores. Seeing a lot of the damage mining has done in Canada however, I have an aversion to disturbing the topsoil for these things. There are places along the Canadian shield where such disturbances have unwittingly released highly radioactive gasses from that ancient crater fallout zone. On the other hand, the popularity of reiki has opened grand scale slush markets of semi-precious stones being inconsequencially hacked out some very delicate ecotopes of Peru and Brazil, to name a few. Things that should be taken into serious consideration if making a purchase. As for gathering these stones yourselves, I shall leave it up to you to chose what manner of approach to the land wights- as their expectations can vary. Follow your instincts.

Ancient European Calendar Systems

THE NEBRA DISK

The almost circular disk has a diameter of approx. 32 cm and a thickness of 4.5 mm in the middle and 1.7 mm at the edge. It weighs approx. 2 kg. Disk is made of bronze, out of a mixture of copper and tin. The copper matched samples taken from a mine in Mitterberg near Mühlbach am Hochkönig in the eastern Alps. This source was verified by its lead isotope signatures. Aside from the very low percent of 2.5 tin content, the 0.2 % traces of arsenic is typical for bronze age metals. It was apparently hammered out of a sheet of bronze and repeatedly heated to avoid lesions. Through this process the bronze takes on a deep brown to black colour. Traces of egg white used to give the bronze a violet hue were also found. The present green coloured layer of corrosion occurred through being in the ground so long.

The almost circular disk has a diameter of approx. 32 cm and a thickness of 4.5 mm in the middle and 1.7 mm at the edge. It weighs approx. 2 kg. Disk is made of bronze, out of a mixture of copper and tin. The copper matched samples taken from a mine in Mitterberg near Mühlbach am Hochkönig in the eastern Alps. This source was verified by its lead isotope signatures. Aside from the very low percent of 2.5 tin content, the 0.2 % traces of arsenic is typical for bronze age metals. It was apparently hammered out of a sheet of bronze and repeatedly heated to avoid lesions. Through this process the bronze takes on a deep brown to black colour. Traces of egg white used to give the bronze a violet hue were also found. The present green coloured layer of corrosion occurred through being in the ground so long.

The appliqués of unbonded gold plate were inlaid and tempered several times. The bronze swords, axes, chisels and the remains of a spiral armband also found in the horde give a date of their burial as approx. 1600 BCE- while the date these items were produced roughly falls between 2100 to 1700 BCE. Particularly unusual for an archaeological artifact is the evidence that the disk was modified several times over the course of its use. First the disk comprised of the round gold "stars", the larger gold sun disk, the sickle moon and the cluster of seven stars. Then two 82° bows were added on the "horizon", of gold from a different source, as indicated by its impurities. One "star" was moved to make room for the bow, while another two were covered by it on the right side of the disk, leaving thus only 30 of them visible. Later the so-called "Sunbark" was added between two parallel curves (again of gold from another region) embossed with fine indentations. Finally before it was buried, the left horizon was missing and 40 small holes were punched along the edge of the disk. What purpose they served is yet uncertain.

The appliqués of unbonded gold plate were inlaid and tempered several times. The bronze swords, axes, chisels and the remains of a spiral armband also found in the horde give a date of their burial as approx. 1600 BCE- while the date these items were produced roughly falls between 2100 to 1700 BCE. Particularly unusual for an archaeological artifact is the evidence that the disk was modified several times over the course of its use. First the disk comprised of the round gold "stars", the larger gold sun disk, the sickle moon and the cluster of seven stars. Then two 82° bows were added on the "horizon", of gold from a different source, as indicated by its impurities. One "star" was moved to make room for the bow, while another two were covered by it on the right side of the disk, leaving thus only 30 of them visible. Later the so-called "Sunbark" was added between two parallel curves (again of gold from another region) embossed with fine indentations. Finally before it was buried, the left horizon was missing and 40 small holes were punched along the edge of the disk. What purpose they served is yet uncertain.

Extensive forensic and isotopic analysis of the Nebra disk and the rest of the bronze objects established beyond a doubt that they all belong to the same horde found buried on the Mittleberg near Nebra. The analysis also established the age and authenticity of the Nebra disk. The age of the swords and tools was also easily recognized by their style compared to similar items found in Hungary. Carbon dating for the disk could not be done as such metals contains no carbons. A fragment of birch bark found on one of the swords however, gave a date between 1600 to 1560 BCE.

The almost circular disk has a diameter of approx. 32 cm and a thickness of 4.5 mm in the middle and 1.7 mm at the edge. It weighs approx. 2 kg. Disk is made of bronze, out of a mixture of copper and tin. The copper matched samples taken from a mine in Mitterberg near Mühlbach am Hochkönig in the eastern Alps. This source was verified by its lead isotope signatures. Aside from the very low percent of 2.5 tin content, the 0.2 % traces of arsenic is typical for bronze age metals. It was apparently hammered out of a sheet of bronze and repeatedly heated to avoid lesions. Through this process the bronze takes on a deep brown to black colour. Traces of egg white used to give the bronze a violet hue were also found. The present green coloured layer of corrosion occurred through being in the ground so long.

The almost circular disk has a diameter of approx. 32 cm and a thickness of 4.5 mm in the middle and 1.7 mm at the edge. It weighs approx. 2 kg. Disk is made of bronze, out of a mixture of copper and tin. The copper matched samples taken from a mine in Mitterberg near Mühlbach am Hochkönig in the eastern Alps. This source was verified by its lead isotope signatures. Aside from the very low percent of 2.5 tin content, the 0.2 % traces of arsenic is typical for bronze age metals. It was apparently hammered out of a sheet of bronze and repeatedly heated to avoid lesions. Through this process the bronze takes on a deep brown to black colour. Traces of egg white used to give the bronze a violet hue were also found. The present green coloured layer of corrosion occurred through being in the ground so long.  The appliqués of unbonded gold plate were inlaid and tempered several times. The bronze swords, axes, chisels and the remains of a spiral armband also found in the horde give a date of their burial as approx. 1600 BCE- while the date these items were produced roughly falls between 2100 to 1700 BCE. Particularly unusual for an archaeological artifact is the evidence that the disk was modified several times over the course of its use. First the disk comprised of the round gold "stars", the larger gold sun disk, the sickle moon and the cluster of seven stars. Then two 82° bows were added on the "horizon", of gold from a different source, as indicated by its impurities. One "star" was moved to make room for the bow, while another two were covered by it on the right side of the disk, leaving thus only 30 of them visible. Later the so-called "Sunbark" was added between two parallel curves (again of gold from another region) embossed with fine indentations. Finally before it was buried, the left horizon was missing and 40 small holes were punched along the edge of the disk. What purpose they served is yet uncertain.

The appliqués of unbonded gold plate were inlaid and tempered several times. The bronze swords, axes, chisels and the remains of a spiral armband also found in the horde give a date of their burial as approx. 1600 BCE- while the date these items were produced roughly falls between 2100 to 1700 BCE. Particularly unusual for an archaeological artifact is the evidence that the disk was modified several times over the course of its use. First the disk comprised of the round gold "stars", the larger gold sun disk, the sickle moon and the cluster of seven stars. Then two 82° bows were added on the "horizon", of gold from a different source, as indicated by its impurities. One "star" was moved to make room for the bow, while another two were covered by it on the right side of the disk, leaving thus only 30 of them visible. Later the so-called "Sunbark" was added between two parallel curves (again of gold from another region) embossed with fine indentations. Finally before it was buried, the left horizon was missing and 40 small holes were punched along the edge of the disk. What purpose they served is yet uncertain.

FIRST PHASE: According to Archaeologist Harald Meller und Astronomer Wolfhard Schlosser the cluster of 7 gold dots likely represent the Pleiades in the constellation of Taurus. vermutlich den Sternhaufen der Plejaden, die zum Sternbild Stier gehören. The other 25 stars however, were only later recognized by other astronomers as reflecting an actual planisphere of the night sky.

The large gold disk is the assumed to represent the sun as well as the full moon, whereas the sickle is the waxing lunar cresent. According to Meller und Schlosser two dates for the visibility of the Pleiades on the west horizon. During the Bronze Age, this was on the 10th of March briefly before nightfall, and on the 17th of October, briefly before dawn. When in March the Moon was in conjunction with the Pleiades, it appeared as a fine sickle just before new moon. In the October conjunction the moon was full. However, given the different lenths of the lunar year as compared to the solar, not every year did this conjunction fall on these dates. By this the disk served as an agrarian reminder for planting and harvesting cycles. According to the Astronomer Rahlf Hansen this device helped Bronze Age farmers coordinate the moon year of 354 days with the sun year of 365 days, in essence keep track of necessary leap years. Similar knowledge is in found in old Babylonian cuniform texts. For this reason skeptics assumed the disk may have been imported, but the measure of 82° for the sun arc on the on the edge of the disk corresponds totally to the latitude of Nebra. Thus, it goes to show that central European astronomers of the time were far more advanced than historians had previously thought.

The large gold disk is the assumed to represent the sun as well as the full moon, whereas the sickle is the waxing lunar cresent. According to Meller und Schlosser two dates for the visibility of the Pleiades on the west horizon. During the Bronze Age, this was on the 10th of March briefly before nightfall, and on the 17th of October, briefly before dawn. When in March the Moon was in conjunction with the Pleiades, it appeared as a fine sickle just before new moon. In the October conjunction the moon was full. However, given the different lenths of the lunar year as compared to the solar, not every year did this conjunction fall on these dates. By this the disk served as an agrarian reminder for planting and harvesting cycles. According to the Astronomer Rahlf Hansen this device helped Bronze Age farmers coordinate the moon year of 354 days with the sun year of 365 days, in essence keep track of necessary leap years. Similar knowledge is in found in old Babylonian cuniform texts. For this reason skeptics assumed the disk may have been imported, but the measure of 82° for the sun arc on the on the edge of the disk corresponds totally to the latitude of Nebra. Thus, it goes to show that central European astronomers of the time were far more advanced than historians had previously thought.

THE GOLDEN HATS

(from Wikipedia)

Golden hats (or Goldhüte) are a very specific and rare type of archaeological artifact from Bronze Age Central Europe. So far, four such objects ("cone-shaped gold hats of the Schifferstadt type") are known. The objects are made of thin sheet gold and were attached externally to long conical and brimmed headdresses which were probably made of some organic material and served to stabilise the external gold leaf. The following Golden Hats are known at present:

Golden Hat of Schifferstadt, found in 1835 at Schifferstadt near Speyer, circa 1400-1300 BC.

Avanton Gold Cone, incomplete, found at Avanton near Poitiers in 1844, c. 1000-900 BC.

Golden Cone of Ezelsdorf-Buch, found near Ezelsdorf near Nuremberg in 1953, circa 1000-900 BC; the tallest known specimen at c. 90 cm.

Berlin Gold Hat, found probably in Swabia or Switzerland, circa 1000-800 BC; acquired by the Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte, Berlin, in 1996.

The hats are associated with the pre-Proto-Celtic Bronze Age Urnfield culture. Their close similarities in symbolism and techniques of manufacture are testimony to a coherent Bronze Age culture over a wide-ranging territory in eastern France and western and southwestern Germany. A comparable golden pectoral was found at Mold, Flintshire, in northern Wales, but this appears to be of somewhat earlier date.

The cone-shaped Golden Hats of Schifferstadt type are assumed to be connected with a number of comparable cap or crown-shaped gold leaf objects from Ireland Comerford Crown, discovered in 1692) and the Atlantic coast of Spain (Gold leaf crowns of Axtroki and Rianxo). Only the Spanish specimens survive.

Unfortunately, the archaeological contexts of the cones are not very clear (for the Berlin specimen, it is entirely unknown). At least two of the known examples (Berlin and Schifferstadt) appear to have been deliberately and carefully buried in antiquity. Although none can be dated precisely, their technology suggests that they were probably made between 1200 and 800 BC.

It is assumed that the Golden Hats served as religious insignia for the deities or priests of a sun cult then widespread in Central Europe. Their use as head-gear is strongly supported by the fact that the three of four examples have a cap-like widening at the bottom of the cone, and that their openings are oval (not round), with diameters and shapes roughly equivalent to those of a human skull. The figural depiction of an object resembling a conical hat on a stone slab of the King's Grave at Kivik, Southern Sweden, strongly supports their association with religion and cult, as does the fact that the known examples appear to have been deposited (buried) carefully.

Attempts to decipher the Golden Hats' ornamentation suggest that their cultic role is accompanied or complemented by a usability as complex calendrical devices. Whether they were really used for such puror simply presented the underlying astronomical knowledge, remains unknown.

The gold cones are covered in bands of ornaments along their whole length and extent. The ornaments - mostly disks and concentric circles, sometimes wheels - were punched using stamps, rolls or combs. The older examples (Avanton, Schifferstadt) show a more restricted range of ornaments than the later ones.

CALENDRICAL FUNCTIONS

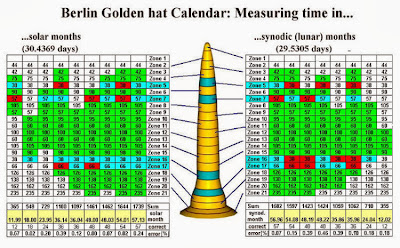

It appears to be the case that the ornaments on all known Golden Hats represent systematic sequences in terms of number and types of ornaments per band. A detailed study of the Berlin example, which is fully preserved, revealed that the symbols probably represent a lunisolar calendar. The object would have permitted the determination of dates or periods in both lunar and solar calendars.

Since an exact knowledge of the solar year was of special interest for the determination of religiously important events such as the summer and winter solstices, the astronomical knowledge depicted on the Golden Hats was of high value to Bronze Age society. Whether the hats themselves were indeed used for determining such dates, or whether they simply represented such knowledge, remains unknown.

The functions discovered so far would permit the counting of temporal units of up to 57 months. A simple multiplication of such values would also permit the calculation of longer periods, eg. metonic cycles. Each symbol, or each ring of a symbol, represents a single day. Apart from ornament bands incorporating differing numbers of rings there are special symbols and zones in intercalary areas, which would have had to be added to or subtracted from the periods in question.

The system of this mathematical function incorporated into the artistic ornamentation has not been fully deciphered so far, but a schematic understanding of the Berlin Golden Hat and the periods it delimits has been achieved.

The large gold disk is the assumed to represent the sun as well as the full moon, whereas the sickle is the waxing lunar cresent. According to Meller und Schlosser two dates for the visibility of the Pleiades on the west horizon. During the Bronze Age, this was on the 10th of March briefly before nightfall, and on the 17th of October, briefly before dawn. When in March the Moon was in conjunction with the Pleiades, it appeared as a fine sickle just before new moon. In the October conjunction the moon was full. However, given the different lenths of the lunar year as compared to the solar, not every year did this conjunction fall on these dates. By this the disk served as an agrarian reminder for planting and harvesting cycles. According to the Astronomer Rahlf Hansen this device helped Bronze Age farmers coordinate the moon year of 354 days with the sun year of 365 days, in essence keep track of necessary leap years. Similar knowledge is in found in old Babylonian cuniform texts. For this reason skeptics assumed the disk may have been imported, but the measure of 82° for the sun arc on the on the edge of the disk corresponds totally to the latitude of Nebra. Thus, it goes to show that central European astronomers of the time were far more advanced than historians had previously thought.

The large gold disk is the assumed to represent the sun as well as the full moon, whereas the sickle is the waxing lunar cresent. According to Meller und Schlosser two dates for the visibility of the Pleiades on the west horizon. During the Bronze Age, this was on the 10th of March briefly before nightfall, and on the 17th of October, briefly before dawn. When in March the Moon was in conjunction with the Pleiades, it appeared as a fine sickle just before new moon. In the October conjunction the moon was full. However, given the different lenths of the lunar year as compared to the solar, not every year did this conjunction fall on these dates. By this the disk served as an agrarian reminder for planting and harvesting cycles. According to the Astronomer Rahlf Hansen this device helped Bronze Age farmers coordinate the moon year of 354 days with the sun year of 365 days, in essence keep track of necessary leap years. Similar knowledge is in found in old Babylonian cuniform texts. For this reason skeptics assumed the disk may have been imported, but the measure of 82° for the sun arc on the on the edge of the disk corresponds totally to the latitude of Nebra. Thus, it goes to show that central European astronomers of the time were far more advanced than historians had previously thought. THE GOLDEN HATS

(from Wikipedia)

Golden hats (or Goldhüte) are a very specific and rare type of archaeological artifact from Bronze Age Central Europe. So far, four such objects ("cone-shaped gold hats of the Schifferstadt type") are known. The objects are made of thin sheet gold and were attached externally to long conical and brimmed headdresses which were probably made of some organic material and served to stabilise the external gold leaf. The following Golden Hats are known at present:

Golden Hat of Schifferstadt, found in 1835 at Schifferstadt near Speyer, circa 1400-1300 BC.

Avanton Gold Cone, incomplete, found at Avanton near Poitiers in 1844, c. 1000-900 BC.

Golden Cone of Ezelsdorf-Buch, found near Ezelsdorf near Nuremberg in 1953, circa 1000-900 BC; the tallest known specimen at c. 90 cm.

Berlin Gold Hat, found probably in Swabia or Switzerland, circa 1000-800 BC; acquired by the Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte, Berlin, in 1996.

The hats are associated with the pre-Proto-Celtic Bronze Age Urnfield culture. Their close similarities in symbolism and techniques of manufacture are testimony to a coherent Bronze Age culture over a wide-ranging territory in eastern France and western and southwestern Germany. A comparable golden pectoral was found at Mold, Flintshire, in northern Wales, but this appears to be of somewhat earlier date.

The cone-shaped Golden Hats of Schifferstadt type are assumed to be connected with a number of comparable cap or crown-shaped gold leaf objects from Ireland Comerford Crown, discovered in 1692) and the Atlantic coast of Spain (Gold leaf crowns of Axtroki and Rianxo). Only the Spanish specimens survive.

Unfortunately, the archaeological contexts of the cones are not very clear (for the Berlin specimen, it is entirely unknown). At least two of the known examples (Berlin and Schifferstadt) appear to have been deliberately and carefully buried in antiquity. Although none can be dated precisely, their technology suggests that they were probably made between 1200 and 800 BC.

It is assumed that the Golden Hats served as religious insignia for the deities or priests of a sun cult then widespread in Central Europe. Their use as head-gear is strongly supported by the fact that the three of four examples have a cap-like widening at the bottom of the cone, and that their openings are oval (not round), with diameters and shapes roughly equivalent to those of a human skull. The figural depiction of an object resembling a conical hat on a stone slab of the King's Grave at Kivik, Southern Sweden, strongly supports their association with religion and cult, as does the fact that the known examples appear to have been deposited (buried) carefully.

Attempts to decipher the Golden Hats' ornamentation suggest that their cultic role is accompanied or complemented by a usability as complex calendrical devices. Whether they were really used for such puror simply presented the underlying astronomical knowledge, remains unknown.

The gold cones are covered in bands of ornaments along their whole length and extent. The ornaments - mostly disks and concentric circles, sometimes wheels - were punched using stamps, rolls or combs. The older examples (Avanton, Schifferstadt) show a more restricted range of ornaments than the later ones.

CALENDRICAL FUNCTIONS

It appears to be the case that the ornaments on all known Golden Hats represent systematic sequences in terms of number and types of ornaments per band. A detailed study of the Berlin example, which is fully preserved, revealed that the symbols probably represent a lunisolar calendar. The object would have permitted the determination of dates or periods in both lunar and solar calendars.

Since an exact knowledge of the solar year was of special interest for the determination of religiously important events such as the summer and winter solstices, the astronomical knowledge depicted on the Golden Hats was of high value to Bronze Age society. Whether the hats themselves were indeed used for determining such dates, or whether they simply represented such knowledge, remains unknown.

The functions discovered so far would permit the counting of temporal units of up to 57 months. A simple multiplication of such values would also permit the calculation of longer periods, eg. metonic cycles. Each symbol, or each ring of a symbol, represents a single day. Apart from ornament bands incorporating differing numbers of rings there are special symbols and zones in intercalary areas, which would have had to be added to or subtracted from the periods in question.

The system of this mathematical function incorporated into the artistic ornamentation has not been fully deciphered so far, but a schematic understanding of the Berlin Golden Hat and the periods it delimits has been achieved.

Early European Shamanism

By Quasizoid

The nature of this practice in paleolithic Europe can be seen in this and other figures that were found in four different caves of the Swabian Alps. Their origins date over a period of 40 to 29 thousand years ago when hunter/gatherers followed the herds of mammoth that once foraged in these regions. Bears and Lions were exalted for their survival skills, so animism involved dressing in their skins and masks to emulate these attributes, essentially psyching onesself up for the hunt. It is from these traditions the beserkers and other forms of shamanism evolved,

The nature of this practice in paleolithic Europe can be seen in this and other figures that were found in four different caves of the Swabian Alps. Their origins date over a period of 40 to 29 thousand years ago when hunter/gatherers followed the herds of mammoth that once foraged in these regions. Bears and Lions were exalted for their survival skills, so animism involved dressing in their skins and masks to emulate these attributes, essentially psyching onesself up for the hunt. It is from these traditions the beserkers and other forms of shamanism evolved,

Amongst various other carvings of mammoths, wildcats, bears, horses and birds, "venus" figurines were also found. These, of course, served as fertility talismans. A flute was also found, that was carved out of a bird bone, so obviously trancing rituals involved more than just drumming back in the early Stone Age.

Amongst various other carvings of mammoths, wildcats, bears, horses and birds, "venus" figurines were also found. These, of course, served as fertility talismans. A flute was also found, that was carved out of a bird bone, so obviously trancing rituals involved more than just drumming back in the early Stone Age.

Looking back to the earliest Celto-Germanic deities, we come across such figures as Cernunnos and Wotan, that remind us of these ancient spiritual practices. Here their predecessor can be seen immortalized on a cliff face in Naquane National Park in Italy:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rock_Drawings_in_Valcamonica

What springs to mind is such names as Herne, Rübezahl and the Perchten traditions still celebrated around the Alps. We know that in old Celto-Germanic trancing rituals, fly agraric and concoctions of various other herbal psychogens were used to enhance the visionary state. "Odin's Sacrifice" was in fact a shamanic ritual of visionary travel to the "Nine Worlds". However, rather than pierce themselves with a yew spear, a brew made of yew fruit (without the deadly poisonous seeds) and herbs was drunk prior to the trancing. We also know that the Berserkers drank similar concoctions in their trancing rituals before heading off to battle. On the cauldron, we see the animal spirits portrayed that the shaman seeks to bond with. One thing seldom mentioned in popular literature, is the snake- but if you look at Jorgamund embracing Middle Earth in the world tree, the meaning becomes perfectly clear; namely transcending the boundaries to the otherworldly. In earliest creation myths this creature is understood as the "Fire Serpent", symbolizing a cosmic force.

Shamanism, however, was not exclusively a man's world in Europe. Rather, like you find in most indigenous tribal societies, women had their own secret practices apart from the men. Although much of their traditions seem to have disappeared over the course of Christian conversion, their origins can be found in the folklore of the goddess "Berchta", the predecessor of Holda/Freya. Given her integral part agrarian culture and its understanding of natural cycles, much was adopted into Catholic practices in association with the Virgin Mary, or renamed after a saint (ie. St. Brigit, St. Barbara etc.) In her role as weaver woman, one can also see associations with the Hellenic goddess Hecate.

The nature of this practice in paleolithic Europe can be seen in this and other figures that were found in four different caves of the Swabian Alps. Their origins date over a period of 40 to 29 thousand years ago when hunter/gatherers followed the herds of mammoth that once foraged in these regions. Bears and Lions were exalted for their survival skills, so animism involved dressing in their skins and masks to emulate these attributes, essentially psyching onesself up for the hunt. It is from these traditions the beserkers and other forms of shamanism evolved,

The nature of this practice in paleolithic Europe can be seen in this and other figures that were found in four different caves of the Swabian Alps. Their origins date over a period of 40 to 29 thousand years ago when hunter/gatherers followed the herds of mammoth that once foraged in these regions. Bears and Lions were exalted for their survival skills, so animism involved dressing in their skins and masks to emulate these attributes, essentially psyching onesself up for the hunt. It is from these traditions the beserkers and other forms of shamanism evolved, Amongst various other carvings of mammoths, wildcats, bears, horses and birds, "venus" figurines were also found. These, of course, served as fertility talismans. A flute was also found, that was carved out of a bird bone, so obviously trancing rituals involved more than just drumming back in the early Stone Age.

Amongst various other carvings of mammoths, wildcats, bears, horses and birds, "venus" figurines were also found. These, of course, served as fertility talismans. A flute was also found, that was carved out of a bird bone, so obviously trancing rituals involved more than just drumming back in the early Stone Age.Looking back to the earliest Celto-Germanic deities, we come across such figures as Cernunnos and Wotan, that remind us of these ancient spiritual practices. Here their predecessor can be seen immortalized on a cliff face in Naquane National Park in Italy:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rock_Drawings_in_Valcamonica

What springs to mind is such names as Herne, Rübezahl and the Perchten traditions still celebrated around the Alps. We know that in old Celto-Germanic trancing rituals, fly agraric and concoctions of various other herbal psychogens were used to enhance the visionary state. "Odin's Sacrifice" was in fact a shamanic ritual of visionary travel to the "Nine Worlds". However, rather than pierce themselves with a yew spear, a brew made of yew fruit (without the deadly poisonous seeds) and herbs was drunk prior to the trancing. We also know that the Berserkers drank similar concoctions in their trancing rituals before heading off to battle. On the cauldron, we see the animal spirits portrayed that the shaman seeks to bond with. One thing seldom mentioned in popular literature, is the snake- but if you look at Jorgamund embracing Middle Earth in the world tree, the meaning becomes perfectly clear; namely transcending the boundaries to the otherworldly. In earliest creation myths this creature is understood as the "Fire Serpent", symbolizing a cosmic force.

Shamanism, however, was not exclusively a man's world in Europe. Rather, like you find in most indigenous tribal societies, women had their own secret practices apart from the men. Although much of their traditions seem to have disappeared over the course of Christian conversion, their origins can be found in the folklore of the goddess "Berchta", the predecessor of Holda/Freya. Given her integral part agrarian culture and its understanding of natural cycles, much was adopted into Catholic practices in association with the Virgin Mary, or renamed after a saint (ie. St. Brigit, St. Barbara etc.) In her role as weaver woman, one can also see associations with the Hellenic goddess Hecate.

Cro-Magnon 28,000 Yrs Old Had DNA Like Modern Humans

ScienceDaily (July 16, 2008) — Some 40,000 years ago, Cro-Magnons — the first people who had a skeleton that looked anatomically modern — entered Europe, coming from Africa. A group of geneticists, coordinated by Guido Barbujani and David Caramelli of the Universities of Ferrara and Florence, shows that a Cro-Magnoid individual who lived in Southern Italy 28,000 years ago was a modern European, genetically as well as anatomically.

The Cro-Magnoid people long coexisted in Europe with other humans, the Neandertals, whose anatomy and DNA were clearly different from ours. However, obtaining a reliable sequence of Cro-Magnoid DNA was technically challenging.

“The risk in the study of ancient individuals is to attribute to the fossil specimen the DNA left there by archaeologists or biologists who manipulated it,” Barbujani says. “To avoid that, we followed all phases of the retrieval of the fossil bones and typed the DNA sequences of all people who had any contacts with them.”

The researchers wrote in the newly published paper: “The Paglicci 23 individual carried a mtDNA sequence that is still common in Europe, and which radically differs from those of the almost contemporary Neandertals, demonstrating a genealogical continuity across 28,000 years, from Cro-Magnoid to modern Europeans.”

The results demonstrate for the first time that the anatomical differences between Neandertals and Cro-Magnoids were associated with clear genetic differences. The Neandertal people, who lived in Europe for nearly 300,000 years, are not the ancestors of modern Europeans.

Tibia fragment. DNA was extracted from this fragment and from skull splinters, and all extracts yielded the same HVR I sequence. (Credit: David Caramelli et al. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002700.g001)

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/07/080715204741.htm

The Cro-Magnoid people long coexisted in Europe with other humans, the Neandertals, whose anatomy and DNA were clearly different from ours. However, obtaining a reliable sequence of Cro-Magnoid DNA was technically challenging.

“The risk in the study of ancient individuals is to attribute to the fossil specimen the DNA left there by archaeologists or biologists who manipulated it,” Barbujani says. “To avoid that, we followed all phases of the retrieval of the fossil bones and typed the DNA sequences of all people who had any contacts with them.”

The researchers wrote in the newly published paper: “The Paglicci 23 individual carried a mtDNA sequence that is still common in Europe, and which radically differs from those of the almost contemporary Neandertals, demonstrating a genealogical continuity across 28,000 years, from Cro-Magnoid to modern Europeans.”

The results demonstrate for the first time that the anatomical differences between Neandertals and Cro-Magnoids were associated with clear genetic differences. The Neandertal people, who lived in Europe for nearly 300,000 years, are not the ancestors of modern Europeans.

Tibia fragment. DNA was extracted from this fragment and from skull splinters, and all extracts yielded the same HVR I sequence. (Credit: David Caramelli et al. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002700.g001)

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/07/080715204741.htm

Neanderthal genes ‘survive in us’

By Paul Rincon

Science reporter, BBC News

Many people alive today possess some Neanderthal ancestry, according to a landmark scientific study.

The finding has surprised many experts, as previous genetic evidence suggested the Neanderthals made little or no contribution to our inheritance.

The result comes from analysis of the Neanderthal genome – the “instruction manual” describing how these ancient humans were put together.

Between 1% and 4% of the Eurasian human genome seems to come from Neanderthals.

But the study confirms living humans overwhelmingly trace their ancestry to a small population of Africans who later spread out across the world.

“[Neanderthals] are not totally extinct, in some of us they live on – a little bit”,

Professor Svante Paabo, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

The most widely-accepted theory of modern human origins – known as Out of Africa – holds that the ancestors of living humans (Homo sapiens) originated in Africa some 200,000 years ago.

A relatively small group of people then left the continent to populate the rest of the world between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago.

While the Neanderthal genetic contribution – found in people from Europe, Asia and Oceania – appears to be small, this figure is higher than previous genetic analyses have suggested.

“They are not totally extinct. In some of us they live on, a little bit,” said Professor Svante Paabo, from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

Professor Chris Stringer, research leader in human origins at London’s Natural History Museum, is one of the architects of the Out of Africa theory. He told BBC News: “In some ways [the study] confirms what we already knew, in that the Neanderthals look like a separate line.

“But, of course, the really surprising thing for many of us is the implication that there has been some interbreeding between Neanderthals and modern humans in the past.”

John Hawks, assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the US, told BBC News: “They’re us. We’re them.

“It seemed like it was likely to be possible, but I am surprised by the amount. I really was not expecting it to be as high as 4%,” he said of the genetic contribution from Neanderthals.

The sequencing of the Neanderthal genome is a landmark scientific achievement, the product of a four-year-long effort led from Germany’s Max Planck Institute but involving many other universities around the world.

The project makes use of efficient “high-throughput” technology which allows many genetic sequences to be processed at the same time.

The draft Neanderthal sequence contains DNA extracted from the bones of three different Neanderthals found at Vindija Cave in Croatia.

Retrieving good quality genetic material from remains tens of thousands of years old presented many hurdles which had to be overcome.

The samples almost always contained only a small amount of Neanderthal DNA amid vast quantities of DNA from bacteria and fungi that colonised the remains after death.

The Neanderthal DNA itself had broken down into very short segments and had changed chemically. Luckily, the chemical changes were of a predictable nature, allowing the researchers to write software that corrected for them.

Writing in Science journal, the researchers describe how they compared this draft sequence with the genomes of modern people from around the globe.

“The comparison of these two genetic sequences enables us to find out where our genome differs from that of our closest relative,” said Professor Paabo.

Those things that made the Neanderthals apparent to us as a population – those things didn’t work

Dr John Hawks, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The results show that the genomes of non-Africans (from Europe, China and New Guinea) are closer to the Neanderthal sequence than are those from Africa.

The most likely explanation, say the researchers, is that there was limited mating, or “gene flow”, between Neanderthals and the ancestors of present-day Eurasians.

This must have taken place just as people were leaving Africa, while they were still part of one pioneering population. This mixing could have taken place either in North Africa, the Levant or the Arabian Peninsula, say the researchers.

Professor Stringer added: “Any functional significance of these shared genes remains to be determined, but that will certainly be a focus for the next stages of this fascinating research.”

The Out of Africa theory contends that modern humans replaced local “archaic” populations like the Neanderthals.

But there are several variations on this idea. The most conservative model proposes that this replacement took place with no interbreeding between modern humans and Neanderthals.

Unique features:

Another version allows for a degree of assimilation, or absorption, of other human types into the Homo sapiens gene pool.

The latest research strongly supports the Out of Africa theory, but it falsifies the most conservative version of events.

The team identified more than 70 gene changes that were unique to modern humans. These genes are implicated in physiology, the development of the brain, skin and bone.

The researchers also looked for signs of “selective sweeps” – strong natural selection acting to boost traits in modern humans. They found 212 regions where positive selection may have been taking place.

The scientists are interested in discovering genes that distinguish modern humans from Neanderthals because they may have given our evolutionary line certain advantages over the course of evolution.

The most obvious differences were in physique: the muscular, stocky frames of Neanderthals contrast sharply with those of our ancestors. But it is likely there were also more subtle differences, in behaviour, for example.

Dr Hawks commented that the amount of Neanderthal DNA in our genomes seemed high: “What it means is that any traits [Neanderthals] had that might have been useful in later populations should still be here.

“So when we see that their anatomies are gone, this isn’t just chance. Those things that made the Neanderthals apparent to us as a population – those things didn’t work. They’re gone because they didn’t work in the context of our population.”

Researchers had previously thought Europe was the region where Neanderthals and modern humans were most likely to have exchanged genes. The two human types overlapped here for some 10,000 years.

The authors of the paper in Science do not rule out some interbreeding in Europe, but say it was not possible to detect this with present scientific methods.

Paul.Rincon-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/8660940.stm

Cheddar Man is my long-lost relative

This story got a lot of coverage, appearing in most of the newspapers. This is the Daily Telegraph's version. A similar treatment appeared in the Independent.

A HISTORY teacher was "overwhelmed" yesterday when scientists told him that he was a direct descendant of a hunter who lived in the Cheddar Gorge 9,000 years ago.

DNA from a tooth in the skull of Cheddar Man, the oldest complete skeleton found in Britain, matched a DNA sample from the mouth of Adrian Targett, 42, a teacher at Kings of Wessex School, Cheddar, Somerset. The matching gene can only be passed on through the female line and its discovery established that Mr Targett descended from Cheddar Man's mother.

He said yesterday: "It is a very strange piece of news to receive. I'm not quite sure how I feel." Mr Targett, an only child who is married but has no children, took part in the experiment along with other staff and pupils at the school. He gave a mouth swab which was studied by scientists at the Institute of Molecular Medicine at Oxford University, who have been studying Cheddar Man for two years and are preparing a genetic map of Britain.

"I was astonished when they said I was a descendant. I took part to make up the numbers," he said.

"Appropriately enough, I am a history teacher but I have to admit I know next to nothing about Cheddar Man. It is not my period. I suppose I should try to include him in my family tree - but going back 9,000 years could take some time. My family have been in these parts for a long time. On my father's side they were farm labourers. In archaeological terms it is very important that this has happened, I am just astonished it has happened to me."

Mr Targett was born in Bristol but has lived in Cheddar since 1981. He and his wife, Catherine, 47, live several hundred yards from Cheddar Caves, where the fossilised remains of his ancestor were uncovered during drainage work in December 1903.

Richard Gough, the then cave owner, opened the site as a tourist attraction and the skeleton was put on display. It remained in Cheddar until the 1980s when the bones were taken to the Natural History Museum. Tests established that the skeleton was of a Mesolithic Man, who lived just after the end of the last Ice Age.

His environment was heavily forested and he probably belonged to a group which moved over a wide area, north to where Bristol is today and south along the Bristol Channel. The landscape would have been inhabited by deer, wild boar, wolves and bears and Cheddar Man would have lived by hunting animals, trapping birds and gathering wild plants. When he died, at a young age, he was given a ritual burial, his body folded into a crouch and placed in a round hole in the caves.

Further excavations have discovered many human remains, some up to 13,000 years old, but none as complete as Cheddar Man's. Dr Bryan Sykes, who discovered the genetic match, said although the discovery was not surprising in scientific terms, it remained an intriguing piece of research. "It is a fascinating demonstration of a direct link between ourselves and our prehistoric ancestors," he said.""We are revealing connections which go far beyond any written record."

He said it was extraordinary that the DNA had survived, but it was carefully extracted and sequenced. "The DNA is like a series of letters, you can check the spelling sequence against people who are living today," he said. "We can see clearly that Cheddar Man and Mr Targett share a close maternal ancestor."

Dr Sykes said the link undermined the theory that modern Europeans were largely descended from peoples who migrated from the East and brought farming techniques with them. "Cheddar Man lived well before the advent of farming and this discovery shows a clear link between us and hunter-gatherers," he said.

Prof Chris Stringer, principal researcher in human origins at the Natural History Museum, said he hoped Dr Sykes would be able to find and record DNA from older remains. Mr Targett's wife had the last word: "Perhaps this explains why he likes his steaks rare," she said.

Daily Telegraph, March 8th 1997

http://www.arcl.ed.ac.uk/a1/stoppress/stop12.htm

THE CHEDDAR MAN AND CANNIBALS MUSEUM

The Cheddar Man and Cannibals Museum explores life in prehistoric Britain with exhibits about survival skills, art, and daily activities in the Stone Age. Guides describe and demonstrate how to make axe heads and how to utilize mammoth tusks in home-building. They also explain how our ancestors ate one another.

Cannibal Cottage is more than just a gruesome horror tour. When the exhibit first opened, it was controversial, particularly for its collection of slaughtered human bones. These remains are nearly thirteen thousand years old and prove that the first humans were cannibals. The museum attempts to contextualize these findings by detailing the history of cannibalism, how and why it might have been necessary, and the evolution of Homo sapiens.

Explorers can also hike to Nature's Cathedral, a quarter mile cave formed by an Ice Age river, and glimpse breathtaking geological wonders. The stalactites and stalagmites in these caverns have been building for hundreds of thousands of years. It was in this area, Gough's cave, that the Cheddar man, Britain's oldest complete skeleton, was discovered. The Mesolithic hunter-gatherer's body was buried there nine thousand years ago. Though the original remains have been moved to London's National History Museum, a replica of the skeleton is still part of the exhibit. Examinations of his body seems to indicate that the Cheddar Man suffered a mysterious and violent death.

http://atlasobscura.com/place/the-cheddar-man-and-cannibals-museum

Neolithic Farmers Brought Deer to Ireland

The origins of the iconic Irish red deer was a controversial topic. Was this species native to Ireland, or introduced?

In a new study that was published 30 March 2012 in the scientific journal Quaternary Science Reviews, a multinational team of researchers from Ireland, Austria, UK and USA have finally answered this question.

Comparing DNA

By comparing DNA from ancient bone specimens to DNA obtained from modern animals, the researchers discovered that the Kerry red deer are the direct descendants of deer present in Ireland 5000 years ago. Further analysis using DNA from European deer proves that Neolithic people from Britain first brought the species to Ireland.

Although proving the red deer is not native to Ireland, researchers believe that the Kerry population is unique as it is directly related to the original herd and are worthy of special conservation status.

A link to the pastFossil bone samples from the National Museum of Ireland, some up to 30,000 years old, were used in the study. Results also revealed several 19th and 20th century introductions of red deer to Ireland, which are in agreement with written records from the same time. At present there is no evidence of red deer in Ireland during the Mesolithic period, 9000 years ago, when humans first settled there.

Although proving the red deer is not native to Ireland, researchers believe that the Kerry population is unique as it is directly related to the original herd and are worthy of special conservation status.

A link to the pastFossil bone samples from the National Museum of Ireland, some up to 30,000 years old, were used in the study. Results also revealed several 19th and 20th century introductions of red deer to Ireland, which are in agreement with written records from the same time. At present there is no evidence of red deer in Ireland during the Mesolithic period, 9000 years ago, when humans first settled there.

The genetic analysis also showed that some of these herds were descended from animals imported from Britain in the 1800s and 1900s, matching the historical records.

The DNA showed that the reds away from Kerry have started to “hybridise” or cross-breed with Sitka deer, a species introduced here in 1860. There is however no such interbreeding for the Kerry red population, Dr Carden added. Sitkas also live in the forests of Killarney but the DNA analysis showed no interbreeding had yet taken place.

Dr Allan McDevitt, from the School of Biology and Environmental Science, University College Dublin, one of the lead geneticists said “We have very few native mammals in Ireland but certainly those that arrived with early humans, such as the red deer, are every bit as Irish as we are.”

Source: School of Biology and Environmental Science, University College Dublin

More information:R F Carden, A D McDevitt, F E Zachos, P C Woodman, P O’Toole, H Rose, N T Monaghan, M G Campana, D G Bradley, C J Edwards (2012). Phylogeographic, ancient DNA, fossil and morphometric analyses reve.... Quaternary Science Reviews. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.02.012

School of Biology and Environmental Science, University College Dublin

The Heritage Council, Ireland

Woodman P.; McCarthy M.; Monaghan N., (1997) The Irish quaternary fauna project: Quaternary Science Reviews, Volume 16, Number 2, 1997 , pp. 129-159 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0277-3791(96)00037-6

http://www.pasthorizonspr.com/index.php/archives/04/2012/neolithic-...

Tags: deer, dna, neolithic

New Light on Stonehenge

By Dan Jones

Photographs by Michael Freeman

Editor’s Note: This article was adapted from its original form and updated to include new information for Smithsonian’s Mysteries of the Ancient World bookazine published in Fall 2009.

The druids arrived around 4 p.m. Under a warm afternoon sun, the group of eight walked slowly to the beat of a single drum, from the visitors entrance toward the looming, majestic stone monument. With the pounding of the drum growing louder, the retinue approached the outer circle of massive stone trilithons—each made up of two huge pillars capped by a stone lintel—and passed through them to the inner circle. Here they were greeted by Timothy Darvill, now 51, professor of archaeology at Bournemouth University, and Geoffrey Wainwright, now 72, president of the Society of Antiquaries of London.

For two weeks, the pair had been leading the first excavation in 44 years of the inner circle of Stonehenge—the best-known and most mysterious megalithic monument in the world. Now it was time to refill the pit they had dug. The Druids had come to offer their blessings, as they had done 14 days earlier before the first shovel went into the ground. “At the beginning we warned the spirits of the land that this would be happening and not to feel invaded,” said one of their number who gave his name only as Frank. “Now we’re offering a big thank-you to the ancestors who we asked to give up knowledge to our generation.”

The Druids tossed seven grains of wheat into the pit, one for each continent, and offered a prayer to provide food for the world’s hungry. The gesture seemed fitting, given the nature of the excavation; while other experts have speculated that Stonehenge was a prehistoric observatory or a royal burial ground, Darvill and Wainwright are intent on proving it was primarily a sacred place of healing, where the sick came to be cured and the injured and infirm restored.

Darvill and Wainwright’s theory rests, almost literally, on bluestones—unexceptional igneous rocks, such as dolerite and rhyolite—so called because they take on a bluish hue when wet or cut. Over the centuries, legends have endowed these stones with mystical properties. The British poet Layamon, inspired by the folkloric accounts of 12th-century cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth, wrote in A.D. 1215:

The stones are great;

And magic power they have;

Men that are sick;

Fare to that stone;

And they wash that stone;

And with that water bathe away their sickness.

We now know that Stonehenge was in the making for at least 400 years. The first phase, built around 3000 B.C., was a simple circular earthwork enclosure similar to many “henges” (sacred enclosures typically comprising a circular bank and a ditch) found throughout the British Isles. Around 2800 B.C., timber posts were erected within the enclosure. Again, such posts are not unusual—Woodhenge, for example, which once consisted of tall posts arranged in a series of six concentric oval rings, lies only a few miles to the east.

Archaeologists have long believed that Stonehenge began to take on its modern form two centuries later, when large stones were brought to the site in the third and final stage of its construction. The first to be put in place were the 80 or so bluestones, which were arranged in a double circle with an entrance facing northeast. “Their arrival is when Stonehenge was transformed from a quite ordinary and typical monument into something unusual,” says Andrew Fitzpatrick of Wessex Archaeology, a nonprofit organization based in Salisbury.

The importance of the bluestones is underscored by the immense effort involved in moving them a long distance—some were as long as ten feet and weighed four tons. Geological studies in the 1920s determined that they came from the Preseli Mountains in southwest Wales, 140 miles from Stonehenge. Some geologists have argued that glaciers moved the stones, but most experts now believe that humans undertook the momentous task.

The most likely route would have required traversing some 250 miles—with the stones floated on rafts, then pulled overland by teams of men and oxen or rolled on logs—along the south coast of Wales, crossing the Avon River near Bristol and then heading southeast to the Salisbury Plain. Alternatively, the stones may have come by boat around Land’s End and along the south coast of England before heading upriver and finally overland to Stonehenge. Whatever the route and method, the immensity of the undertaking—requiring thousands of man-hours and sophisticated logistics—has convinced Darvill and Wainwright that the bluestones must have been considered extraordinary. After all, Stonehenge’s sarsens—enormous blocks of hard sandstone used to build the towering trilithons—were quarried and collected from the Marlborough Downs a mere 20 miles to the north.

The two men have spent the last six years surveying the Preseli Mountains, trying to ascertain why Neolithic people might have believed the stones had mystical properties. Most were quarried at a site known as Carn Menyn, a series of rocky outcrops of white-spotted dolerite. “It’s a very special area,” says Wainwright, himself a Welshman. “Approaching Carn Menyn from the south you go up and up, then all of a sudden you see this rampart composed of natural pillars of stone.” Clearly, Carn Menyn inspired the ancients. Gors Fawr, a collection of 16 upright bluestones arranged in a circle, sits at the bottom of a Carn Menyn hill.

But Darvill and Wainwright say the real turning point came in 2006, when the pair looked beyond Carn Menyn’s rock formations and began studying some springs around the base of the crags, many of which had been altered to create “enhanced springheads”—natural spouts had been dammed up with short walls to create pools where the water emerged from the rock. More important, some of the springheads were adorned with prehistoric art.

“This is very unusual,” says Wainwright. “You get springs that have funny things done to them in the Roman and Iron Age periods, but to see it done in the prehistoric period is rare, so we knew we were on to something.” In his history of Britain, Geoffrey of Monmouth noted that the medicinal powers of Stonehenge’s stones were stimulated by pouring water over them for the sick to bathe in. Indeed, many of the springs and wells in southwest Wales are still believed to have healing powers and are used in this way by local adherents to traditional practices. As Wainwright recalls, “The pieces of the puzzle came together when Tim and I looked at each other and said, ‘It’s got to be about healing.’”

Once the archaeologists concluded that the ancients had endowed the Carn Menyn rocks with mystical properties, “franchising” them to Stonehenge made sense. “Its intrinsic power would seem to be locked into the material from which it was made and, short of visiting Carn Menyn, which might not have been always feasible, the next best step would have been to create a shrine from the powerful substance, the stone from Carn Menyn itself,” says Timothy Insoll, an archaeologist at the University of Manchester. He has documented similar behavior in northern Ghana, where boulders from the Tonna’ab earth shrine—similarly invested with curative properties—have been taken to affiliated shrines at new locations.

Evidence that people made healing pilgrimages to Stonehenge also comes from human remains found in the area, most spectacularly from the richest Neolithic grave ever found in the British Isles. It belonged to the “Amesbury Archer”—a man between 35 and 45 years old who was buried about five miles from Stonehenge between 2400 and 2200 B.C. with nearly 100 possessions, including an impressive collection of flint arrowheads, copper knives and gold earrings.

The bones of the Amesbury Archer tell a story of a sick, injured traveler coming to Stonehenge from as far away as the Swiss or German Alps. The Archer’s kneecap was infected and he suffered from an abscessed tooth so nasty that it had destroyed part of his jawbone. He would have been desperate for relief, says Wessex Archaeology’s Jacqueline McKinley.

Just 15 feet from where the Amesbury Archer was buried, archaeologists discovered another set of human remains, these of a younger man perhaps 20 to 25 years old. Bone abnormalities shared by both men suggest they could have been related —a father aided by his son, perhaps. Had they come to Stonehenge together in search of its healing powers?

Remarkably, although Stonehenge is one of the most famous monuments in the world, definitive data about it are scarce. In part, this is because of the reluctance of English Heritage, the site’s custodian, to permit excavations. Current chronologies are based largely on excavations done in the 1920s, buttressed by work done in the ’50s and ’60s. “But none of these excavations were particularly well recorded,” says Mike Pitts, editor of British Archaeology and one of the few people to have led excavations at Stonehenge in recent decades. “We are still unsure of the detail of the chronology and nature of the various structures that once stood on the site.”

To strengthen their case for Stonehenge as a prehistoric Lourdes, Darvill and Wainwright needed to establish that chronology with greater certainty. Had the bluestones been erected by the time the Amesbury Archer made his pilgrimage to the megaliths? Establishing the timing of Stonehenge’s construction could also shed light on what made this site so special: with so many henges across Britain, why was this one chosen to receive the benedictions of the bluestones? Such questions could be answered only by an excavation within Stonehenge itself.

Darvill and Wainwright were well placed for such a project. Wainwright had been English Heritage’s chief archaeologist for several years. In 2005, Darvill had worked with the organization on a plan for research at the monument— “Stonehenge World Heritage Site: An Archaeological Research Framework”—which made the case for small-scale, targeted excavations. Following these guidelines, Darvill and Wainwright requested official permission for the archaeological equivalent of keyhole surgery in order to study part of the first bluestone setting on the site.

And so, under an overcast sky blanketing Salisbury Plain and under the watchful eye of English Heritage personnel and media representatives from around the world, Darvill and Wainwright’s team began digging in March 2008. Over the previous weekend, the team had set up a temporary building that would serve as a base for operations and marked out the plot to be excavated. Next to the site’s parking lot a newly erected marquee broadcast a live video feed of the action—and offered a selection of souvenir T-shirts, one of which read, “Stonehenge Rocks.”

The trench that Darvill and Wainwright marked out for the excavation was surprisingly small: just 8 by 11 feet, and 2 to 6 feet deep in the southeastern sector of the stone circle. But the trench, wedged between a towering sarsen stone and two bluestones, was far from a random choice. In fact, a portion of it overlapped with the excavation carried out by archaeologist Richard Atkinson and colleagues in 1964 that had partially revealed (though not for the first time) one of the original bluestone sockets and gave reason to believe that another socket would be nearby. In addition, Bournemouth University researchers had conducted a ground-penetrating radar survey, providing further assurance that this would be a productive spot.

Wainwright had cautioned me that watching an archaeological dig was like watching paint dry. But while the work is indeed slow and methodical, it is also serene, even meditative. An avuncular figure with a white beard framing a smiling, ruddy face, Wainwright joined Bournemouth University students operating a large, clattering sieve, picking out everything of interest: bones, potsherds and fragments of sarsen and bluestone.

Some days a strong wind blew through the site, creating a small dust bowl. Other days brought rain, sleet and even snow. As material was excavated from the trench and sifted through the coarse sieve, it was ferried to the temporary building erected in the parking lot. Here other students and Debbie Costen, Darvill’s research assistant, put the material into a flotation tank, which caused any organic matter—such as carbonized plant remains that could be used for radiocarbon dating—to float to the surface.

By the end of the excavation, contours of postholes that once held timber poles and of bedrock-cut sockets for bluestones were visible. In addition, dozens of samples of organic material, including charred cereal grains and bone, had been collected, and 14 of these were selected for radiocarbon dating. Although it would not be possible to establish dates from the bluestone sockets themselves, their age could be inferred from the age of the recovered organic materials, which are older the deeper they are buried. Environmental archaeologist Mike Allen compared the positions and depths of the bluestone sockets with this chronology. Using these calculations, Darvill and Wainwright would later estimate that the first bluestones had been placed between 2400 and 2200 B.C.—two or three centuries later than the previous estimate of 2600 B.C.

That means the first bluestones were erected at Stonehenge around the time of the Amesbury Archer’s pilgrimage, lending credence to the theory that he came there to be healed.

Among other finds, the soil yielded two Roman coins dating to the late fourth century A.D. Similar coins have been found at Stonehenge before, but these were retrieved from cut pits and a shaft, indicating that Romans were reshaping and altering the monument long after such activities were supposed to have ended. “This is something that people haven’t really recognized before,” says Darvill. “The power of Stonehenge seems to have long outlasted its original purpose, and these new finds provide a strong link to the world of late antiquity that probably provided the stories picked up by Geoffrey of Monmouth just a few centuries later.”

As so often happens in archaeology, the new findings raise nearly as many questions as they answer. Charcoal recovered by Darvill and Wainwright—indicating the burning of pine wood in the vicinity—dates back to the eighth millennium B.C. Could the area have been a ritual center for hunter-gatherer communities some 6,000 years before the earthen henge was even dug? “The origins of Stonehenge probably lie back in the Mesolithic, and we need to reframe our questions for the next excavation to look back into that deeper time,” Darvill says.

The new radiocarbon dating also raises questions about a theory advanced by archaeologist Mike Parker Pearson of the University of Sheffield, who has long suggested that Stonehenge was a massive burial site and the stones were symbols of the dead—the final stop of an elaborate funeral procession by Neolithic mourners from nearby settlements. The oldest human remains found by Parker Pearson’s team date to around 3030 B.C., about the time the henge was first built but well before the arrival of the bluestones. That means, says Darvill, “the stones come after the burials and are not directly associated with them.”

Of course it’s entirely possible that Stonehenge was both—a great cemetery and a place of healing, as Darvill and Wainwright willingly admit. “Initially it seems to have been a place for the dead with cremations and memorials,” says Darvill, “but after about 2300 B.C. the emphasis changes and it is a focus for the living, a place where specialist healers and the health care professionals of their age looked after the bodies and souls of the sick and infirm.” English Heritage’s Amanda Chadburn also finds the dual-use theory plausible. “It’s such an important place that people want to be associated with it and buried in its vicinity,” she says, “but it could also be such a magical place that it was used for healing, too.”

Not everyone buys into the healing stone theory. “I think the survey work [Darvill and Wainwright are] doing in the Preseli hills is great, and I’m very much looking forward to the full publication of what they’ve found there,” says Mike Pitts. “However, the idea that there is a prehistoric connection between the healing properties of bluestones and Stonehenge as a place of healing does nothing for me at all. As far as I’m concerned, it’s a fairy story.” Pitts also wants to see more evidence that people suffering from injuries and illness visited Stonehenge. “There are actually very few—you can count them on one hand—human remains around and contemporary with Stonehenge that haven’t been cremated so that you could see what injuries or illnesses they might have suffered from,” he says. “For long periods in the Neolithic we have a dearth of human remains of any kind.”

For his part, Wainwright believes that no theory will ever be fully accepted, no matter how convincing the evidence. “I think what most people like about Stonehenge is that nobody really knows why it was built, and I think that’s probably always going to be the case,” he says. “It’s a bloody great mystery.”

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/light-on-stonehen...

Discovery sheds new light on Stonehenge